- Home

- Tom Powers

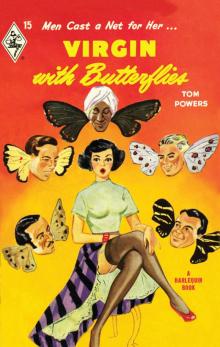

Virgin With Butterflies

Virgin With Butterflies Read online

Dear Reader,

Harlequin is celebrating its sixtieth anniversary in 2009 with an entire year’s worth of special programs showcasing the talent and variety that have made us the world’s leading romance publisher.

With this collection of vintage novels, we are thrilled to be able to journey with you to the roots of our success: six books that hark back to the very earliest days of our history, when the fare was decidedly adventurous, often mysterious and full of passion—1950s-style!

It is such fun to be able to present these works with their original text and cover art, which we hope both current readers and collectors of popular fiction will find entertaining.

Thank you for helping us to achieve and celebrate this milestone!

Warmly,

Donna Hayes,

Publisher and CEO

The Harlequin Story

To millions of readers around the world, Harlequin and romance fiction are synonymous. With a publishing record of 120 titles a month in 29 languages in 107 international markets on 6 continents, there is no question of Harlequin’s success.

But like all good stories, Harlequin’s has had some twists and turns.

In 1949, Harlequin was founded in Winnipeg, Canada. In the beginning, the company published a wide range of books—including the likes of Agatha Christie, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, James Hadley Chase and Somerset Maugham—all for the low price of twenty-five cents.

By the mid 1950s, Richard Bonnycastle was in complete control of the company, and at the urging of his wife—and chief editor—began publishing the romances of British firm Mills & Boon. The books sold so well that Harlequin eventually bought Mills & Boon outright in 1971.

In 1970, Harlequin expanded its distribution into the U.S. and contracted its first American author so that it could offer the first truly American romances. By 1980, that concept became a full-fledged series called Harlequin Superromance, the first romance line to originate outside the U.K.

The 1980s saw continued growth into global markets as well as the purchase of American publisher, Silhouette Books. By 1992, Harlequin dominated the genre, and ten years later was publishing more than half of all romances released in North America.

Now in our sixtieth anniversary year, Harlequin remains true to its history of being the romance publisher, while constantly creating innovative ways to deliver variety in what women want to read. And as we forge ahead into other types of fiction and nonfiction, we are always mindful of the hallmark of our success over the past six decades—guaranteed entertainment!

Virgin with Butterflies

Tom Powers

www.millsandboon.co.uk

TOM POWERS

was born in Kentucky on July 7, 1890. He first made a name for himself in musicals on Broadway, then moved to more dramatic theater productions. In 1944 he agreed to appear in the movie Double Indemnity, and spent the rest of his career in front of the camera. He was also an author, writing fiction, poetry and an autobiography. He died in California in 1955.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER ONE

THIS WHOLE ADVENTURE started when I met the gentleman from India. I didn’t know anything about India that first night he bought the cigarettes from me, and neither did Millie.

Millie’s the other cigarette girl, the one that was at the café selling cigarettes before me—only they had to let her quit because she was getting ready to have a baby. But she still hung around the café nights, looking to see if the feller wouldn’t maybe come back that had gotten her that way.

Anyway, she didn’t know what to make of this gentleman, either. He spoke soft and was not like most of the slickers that come to the café; he was more of a gentleman, with plenty of money and a ring with a red set in it that Millie said was a bum flash, though I don’t know how she could be sure it was fake.

But Moe, the waiter, used to be a jeweler on the other side of the ocean. But Hitler’s police cut off his thumbs, so he couldn’t be a jeweler anymore, as it seems that you’ve got to have thumbs to be a jeweler. Well, Moe said it was a ruby, and I guess it was. And I guess that’s what was the cause of what I’m going to tell about, the cause of everything that happened to me during all those months that me and this gentleman was together, and that got me into the papers even more than when I had been in court back home all those times at my brother Willie’s trials. It was knowing this gentleman that finally pretty near got me in the movies even, though not quite I’m proud to say.

But that first night he came in I didn’t even notice him or his ruby. I was trying to get past the big table, the one over next to the juke box, where five smart guys were drinking some Mexican stuff that Butch had sent Snowball out for. They had money all right, and sharp-cut suits and watch chains. But their hands was hot. And they had thumbs for pinching, all right. And I didn’t like the fat one with pimples at all.

Still I knew I better not get ’em sore or Butch wouldn’t like it, them sending Snowball all the time for some more of that Tokeeya at five bucks a crack. But I finally made a joke like I do sometimes when I get in a tight spot with guys, and that made the other four laugh at the fat pimply one, and hit him with their fists on the shoulder, and so I had kind of won, see? I forget what I said. Things just come to me when I need help bad with smart guys, things that sound simple when you think of ’em afterwards.

Well, as I said, I was skirting around ’em when Millie, sitting there all puffed out, drinking her fourth soda, gave me the eye and jerked her head towards this gentleman. And before I knew it I looked at him with my mouth open.

He had a cup of coffee and a spoon across it. In the spoon was a lump of sugar and it was burning. It reminded me of the sterno Ma used to put under her curling iron when I was a kid back in Mattoon—before she broke it and had to use the poker.

I didn’t see the brandy glass, and even if I had of seen it I guess I didn’t know, at that time, about people burning brandy like what he was doing. Honest, if the cigarette tray wasn’t hung on me by the strap I would of dropped it right on the floor.

I want to tell all of this just like it happened, see? But now I’ve wrote it down it don’t sound real—that about the rubies and him and all. It sounds like some third-run double feature. When I think of all the places him and me went to and all the people we met in Africa and Mexico and all, and how we was always headed for his home town in India, and who we met there and the clothes I wore and how I got to be called The Mystery Woman in the headlines under my pictures, it is more like them cheap sensational movies than what they are theirselves.

But I don’t want to write it sensational, see? Or to make it seem like I wasn’t scared, not only of the places, but of the people and animals. When you see lions and tigers sleeping on their sides in a zoo, with flies walking on ’em or maybe them flicking a fly off of ’em with their tail, you don’t know what wild foreign animals are like. You don’t know animals until you have met a wild lion without any cage to hold it—especially when you’ve got hold of the lion’s tail—or until you’re riding a camel that’s not in any circus and it turns around and bites your toe.

And the guys—say! These toughies we’ve got over here think they are the cat’s meow. But, honest, when it comes to going after a girl there’s things they never even read about.

&nb

sp; Well, where was I? Oh, yes. The Indian gentleman was sitting there in Butch’s Café, looking into the blue flame like a fortune teller in a street carnival. And he looks up and says, “Please,” as soft as petting a sick kitten. And, “Cigarette,” he says, holding the spoon steady with his right hand and reaching with his left in his vest pocket for change.

It was then I saw the set in his ring. “He’s a phony.” That’s what Millie’s look had said, but I knew right away he wasn’t. “What kind?” I says and “What kind you say,” he says. And I knew without him telling me that he didn’t know what kinds we got in this country because of him being a foreigner, see? And I knew he hadn’t never been here before and this time not long enough to have ever bought even one pack. Of course I didn’t know then who he was, or that such people don’t buy cigarettes or he would of learned the name of a kind to ask for. And I knew, too, that he might be dumb in our language but he wasn’t dumb in whatever language he did talk. And I knew this gentleman wasn’t any phony.

So, I give him a pack of Parliaments and opened it for him and stuck one out. And he took it, putting four bits on the table. He dipped the tip of the cigarette into the coffee and then put it in his mouth and leaned over and lit it in the blue flame that was beginning to sputter in the spoon. And the smoke came out of his nose, slow. And he looked up at me with big brown eyes, just exactly like a spaniel dog my aunt Helga had named Spot. He never smiled at all, just looked straight at me and pushed the change back at me when I put it on the table. He had the saddest face I ever saw. He wasn’t a big gentleman, or a strong-looking one. Kind of little he was, and spindly in his black suit and a black tie. It was a kind of a tux, but not very.

He had a kind of a button in his lapel, only it wasn’t like a Wilkie campaign button, but was more like a water lily. Little and kind of enamel, it was. Pretty. I know now it was a lotus flower and it sure meant something where he come from, because of the way the Five Great Men, as he called ’em, looked at it that awful day we got to the cathedral, or whatever they call it, in the jungle behind that huge stone-woman god, after we finally did get all the way to India.

He had on the other clothes and the gold slippers by that time, and the hat on his head. Oh yes, that button meant something. You could tell from the little awed eyes of four of the great men, when they came up to us and touched their foreheads with three of their fingers and bowed like Catholics to a saint, though they wasn’t Catholics. I didn’t know what it was all about, of course, so I just sat and watched. Then they touched the other great man, making five, and even though he was blind and deaf, he showed great respect, too, after he was led up to the big, cold stone chair we was sitting on. He felt with his little brown fingers this lotus flower and then he touched his forehead with three of his fingers and bowed even lower than the other four had bowed.

He wasn’t blind from being old, for he was the youngest of the lot, but across where his eyes had been was scars, new ones. And I remember when it come over me that this littlest great man of the five had most likely had his eyes burnt out, and my stomach went all butterflies.

I always did have a weak stomach. As my pop said, instead of crying like other kids when anything hurt my feelings or things got too scary for me, I’d never break down or squall, like Willie, but I would just spit up whatever I had eaten. But that time I didn’t and a lot of times I didn’t, either, when I could of, easy.

Well, there I stood in Butch’s Café with the Indian gentleman looking at me as if I was the ghost of Lot’s wife turned into a cellar of salt.

I guess I better tell about how I look. Pop’s pop come over from the old country, Sweden I guess it was, ’cause that’s where the Swedes come from and my grandpop he was a Swede. And Pop always said that’s where I got my hair, and I guess it was. They all called me Cotton Top when I was a kid. When I was getting my education, I studied to be a beautician—you know, in a beauty shop.

But after all the talk about our family in the papers, I wanted to get away from Mattoon—who wouldn’t? That’s why I came to Chicago. But too much beauty shop, I guess, is why I would never put a hot iron to my hair. My hair is off platinum and has got a natural wave. Millie was always telling me after I come up here, away from Mattoon, that I ought to do just a little more to it so it would be on platinum, which is the rage. But not me, I won’t even fix it except to twist it into a knot on the back of my neck, which is long and can stand it.

My nails are in good shape and they ought to be after the study and the abuse I took learning to do other people’s, painting and polishing. But I never forgot Pop saying that a red-fingered girl looked like she had been “clawing a cadaver.” That’s what Pop said. I’ll never forget the word, the way Pop said it.

I guess cadaver is a Swede word. Pop knows a lot of words nobody else ever heard of.

Well, that’s why I wouldn’t ever do my nails with red on ’em. I keep ’em nice, but no cadaver did I look like I had been clawing. Pop kept me from lots of things, I guess, but he never told me not to, not Pop.

Ma frowned and primped up her mouth over what she called badness. But Ma never kept anybody from doing anything, especially Willie. But I was Pop’s girl and Willie was Ma’s boy. So Willie didn’t get saved from anything and I got saved from some things, like hair and nails and lips—that Millie was always telling me I ought to do more with those, too. But “What’s the use,” I told Millie. “My lips are red anyway and always was so what’s the use? If a barn is red, what’s the use of painting it red?” That’s what I told her. I didn’t say, “Look at you now, Millie, from painting your lips,” but I could of.

I tell all of this because it seems that the Indian gentleman like it that way; I mean without paint and dye and nails red. Anyway, I guess he did, but I didn’t know all that, not till after.

Well, let me see, how can I tell it? So much happened that night, so quick, after it got started.

There I stood in the white satin uniform. Well, it wasn’t exactly a uniform, just a white satin formal, with a plain, round neckline and long sleeves. Modest, see? But tight over the bust and hips. Butch said his customers had seen enough bare skin. So his idea was to cover up but make it tight. Poor Millie, no wonder she lost her job. But the skirt flared to the floor, full, so you could walk. If it hadn’t, I guess that poor Indian gentleman wouldn’t be alive now—I’d of never been able to drag him across that sidewalk and into Jeff’s taxi, not before the cops got there, anyhow.

Well, it seems that while he was looking at me and I was watching him light his Parliament in the blue flame, the fat pimply one of the guys drinking the Tokeeya had gotten up and followed me over. But I didn’t see he was following me, and then before you could think, there he was. And I felt his hand on me under the arm. And I must of showed in my face that it gave me a scare, like I told you. That’s the kind of times that my stomach does like I said.

It’s hard to get away from guys like that without making Butch mad. I mean when they’re drinking. Well, it must of showed in my face, for this little brown gentleman put down his cigarette and stood up. I wanted to say, “Sit down.” But this pimply guy had seen him over my shoulder and then it was too late.

“What’s the matter, pal?” he says to the little gentleman, who walked two steps towards us and took Pimples’ fat hand in his slim hand and lifted it off of me. I didn’t look around but I heard the other guys’ chairs scrape back as they got up.

When the pimply guy took hold of the little man I heard Millie yell. And then the other guys were there. And I saw the little gentleman rise up off of the floor, with the pimply guy holding him up with his left hand. Holding both sides of the little gentleman’s black coat he was. And I saw his right fist clinched up, fat and sleek, but big and strong, too. And I saw one of the other guys with the empty Tokeeya bottle holding it by the neck. And the little gentleman’s brown eyes, not afraid at all, but just sad, like my aunt Helga’s spaniel. And then Moe got to the switch and the lights blacked out, and the

place went crazy.

I heard the bottle break on what sounded like a head and I was knocked around like a train had hit me, nearly choking until I got my neck out of the strap of the cigarette tray. My little apron was tore off and my arm was twisted and somebody’s fist shot past my face so fast I could feel the wind of it. Then I was kneeling on broken glass and I thought I was bleeding.

And then I had him around the waist and I remember how I thought “Gee, but he’s a thin, little man.” And as I got up somebody stepped with a big foot right on my in-step. But I felt my hands slide up under his arms and the little lotus flower cut my wrist, but I had ahold of him and I dragged him out from where they was all sprawling and kicking and hitting. And we was out of the door and across the sidewalk to Jeff and his taxi and Jeff was swearing words he was always so careful never to say before us girls. Because Jeff was from Texas and had been a cowboy, and cowboys are very careful what they let womenfolk hear them say.

But Jeff was scared about me, I guess, though he’d never let on to me. And there I was praying to God about my butterflies and Jeff saying, “Who started the fight?” And me saying, like Pop, “Never mind who started the fight, big boy, you start the cab.” And him doing it, and me feeling the cold wind on me through that one layer of satin.

CHAPTER TWO

JEFF KEPT DRIVING TOWARDS the lake, not even stopping for the lights because we didn’t want to get hauled in. And he kept talking to me over his shoulder till we just missed, by a mudguard, being messed up by the Michigan Avenue traffic. “Which way now?” Jeff says, and “Hadn’t we better take him and lose him outside some joint?” And a lot more, finishing up with that he hoped this would teach me that Butch’s was no place for a gal like me.

Virgin With Butterflies

Virgin With Butterflies