- Home

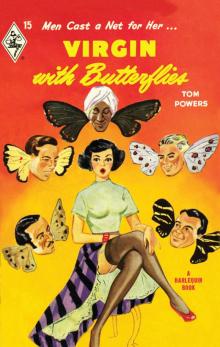

- Tom Powers

Virgin With Butterflies Page 5

Virgin With Butterflies Read online

Page 5

“Who are you?” I says.

“Yanci,” he says, and then I knew why he couldn’t talk plain. Yanci’s was the lip Pimples had busted.

“I came in the window,” he says. “When we started to fix the operator, she gives out that this is a cheap room, see, and that these cheap rooms here ain’t got no phones in them, so I came up. But there was another guy that came up in the elevator with me, and he got out at this floor, too, a little bit ahead of me, and he stopped at Pimples’ door. So I climbed out of the hall window onto the fire escape, see? And I listened at this window. It was open and dark, so I got in. What’s cooking?” he says.

“He knocked on the hall door,” I says. “He’s talking to Pimples now.”

“Who is he?” he says.

“How would I know?” I says. “What did he look like?”

But just then we heard Pimples’ voice, mad as a hornet, yelling, “Get the hell out of here before I poke you, see?” And we both kept right still and listened. This other man, whoever he was, laughed loud and drunk sounding, and then we heard something that sounded like somebody had crashed on the floor hard. Then there was a hand on the knob of the bathroom door. Yanci, like a cat, went back into the dark corner under the window. The door opened and the light was hitting me in the eyes so bright I couldn’t see right away who it was standing there, laughing like a silly drunk, saying, “Come out, Lady Teazel, come out.” First I thought he said Lady Teaser, but it wasn’t that, I heard it plain. And it was Mr. Wens, drunker than you would think anybody could ever get in such a little while.

So I came out and there was Pimples upside down—Mr. Wens must have pushed him into a chair that fell over backwards. So I shut the bathroom door and Mr. Wens kept laughing. I could see Pimples must have hit his head hard against the wall, because he sure looked groggy. And then I saw the ring on the floor. Wens was weaving back and forth and laughing.

“Look at him,” he says. “Just a little push. I came up to give you your winnings,” he says, “and he wasn’t polite, so I pushed him.” And he took a double handful of blue chips out of his coat pockets. “Here,” he says, and he poured ’em into my hands.

“Look,” he says, “you sure were lucky.”

I took ’em and poured the blue chips all over Pimples.

“There!” I says, and I picked up the ring.

“Good!” says Mr. Wens. “Come on,” and he opened the hall door. As we went out, I turned around.

“That’ll more than pay you, Pimples,” I says and I followed Mr. Wens out into the hall. He shut the door, but not before I saw Yanci come darting out of the bathroom like a ferret and start scooping up the blue chips.

Just as we got to the head of the stairs, the elevator door opened down the hall and the Beaver got out with the other two toughies close behind him, but they didn’t see us because Mr. Wens grabbed my hand and pulled me down the steps faster than any drunk could possibly go.

As we got to the second floor and started down towards the lobby, we heard a loud slap on bare skin, and a girl’s giggle come over a transom, “Don’t stop, Mr. Grossi, don’t stop.”

“Quite a place,” says Mr. Wens, and he wasn’t drunk at all now.

CHAPTER FIVE

WE SLOWED UP AS WE GOT to where people could see us and we walked out of the door onto the dark sidewalk. As we came out, a motor made a quick speeding up sound and a big black car slid up and stopped. The door opened and Mr. Wens pushed me in.

The door slammed and the car slid away from Mulloy’s as Mr. Wens and I sat on the two jump seats. I was just about to heave a sigh of relief when I looked in front of us at the backs of two big men in black coats and hats, and I saw that their necks were brown.

I glanced at the two men in the seat behind us, and they were brown men with black coats and hats, too, and so I knew what car it was we were in.

I looked at Mr. Wens and he was grinning. “Where did they come from?” I says.

“You almost ran over ’em in that dark alley out back of the café,” he says.

“Who are they?” I says.

“Indians,” he says.

“Do you know them?”

“We were never properly introduced,” he says, “because they can’t speak English, but we nod to each other in passing.”

And that’s how it went, he kept kidding and wouldn’t tell me nothing.

“You’re quite a gal,” he says. “And I have to ask you something before we get to where we’re going. Do you know what you have in your hand?”

“Yes,” I says.

“Do you know what it’s worth?”

“No,” I says. Just then we were going north over a Michigan Avenue bridge.

“Well,” he says, “it’s worth about as much as that,” and he pointed to the Wrigley Building.

“Do they know that?” I says, nodding at the quartet that was all around us.

“Yes,” he says.

“Do they know I have it?”

“They hope you have it, but don’t show it to ’em or they’ll all four kiss you at once.”

“Do you know the little gentleman that had it hung around his neck?” I says.

“Yes,” he says, “he does speak English, so we were formally introduced.”

“Are you working with these men?” I says.

“Yes,” he says.

“And you and they,” I says, “must have been trying to get it away from the little gentleman,” I says.

“We was just watching him,” he says.

I couldn’t make him out. He still looked like some society playboy—no hat, and his tux didn’t look like a rented waiter’s suit or that of a movie actor with too wide shoulders and too pinched waist. “Was you with them in the alley?” I says.

“I was watching the front of Butch’s place,” he says, “in case you came out that way. They picked me up as they followed you around out of the alley. That’s how I got to Mulloy’s before you did.”

I remembered reading in stories that jewelry thieves were different, better educated than the ones that deal in other stuff, more genteel; they got to be.

“I guess these men would kill me to get it away from me,” I says.

“You’re all right as long as you don’t try to run away,” he says, and he lit a cigarette. “Oh, sorry,” he says, “want one?”

“No thanks,” I says.

“You are a game kid,” he says, “and I want you to do something you may not want to.”

“What?” I says.

“How’d you like to go to Mexico?”

“I can’t,” I says. “What for?”

“Well, now listen—quick, before we get to where we’re going. I feel flattered you’d think I had brains enough to be the mastermind of these mystery-story Indians, but I got to tell you the truth. I’m not the boss. My boss is a pretty smart guy. He’s a gent by the name of Hoover,” he says, “and his boss is his Uncle Sam.”

Before I could say a word, the car stopped, and I was back at the Drake again.

Mr. Wens got out and reached in to help me. The four men sat still, looking like statues, and I went with him straight to the elevator.

“It’s stolen,” I thought, “and I’ve got it.” Then I realized, “And he’s got me. Poor Pop, after all he’s been through.”

I could see him that first day of Willie’s trial, and every day after until it was over, sitting there, listening. Then they called Uncle Ulrich as a witness, and what a witness Uncle Ulrich turned out to be against our side. Of course Pop was grieving that his boy would do such a thing.

And now that Pop was really starting to get a little old, here I was, being taken into this big hotel by a federal man with a ring worth the Wrigley Building that he had seen me grab off of a drunk gangster. And him taking me now to the owner of it to identify it before taking me off to jail.

These were the thoughts I was thinking as we came across the lobby.

He took my arm and we stepped into the elevator, and it started up. There

were morning papers in neat piles on the bench across the back of the elevator. I looked down at them, and what was looking up at me from a picture on that morning paper, but the little gentleman to whose upstairs parlor Mr. Wens was taking me.

Mr. Wens looked, too, at the paper, and then he looked at me and grinned. So he picked up the paper and gave the man a quarter and held the paper so I could read what it said over the picture.

Son of Indian Prince Visits Chicago, it said over the picture, and under it, “Prince Halla Bandah Rookh,” it says, “second son of ruler of Indian principality was greeted by mayor at airport, breaking his journey to Mexico and South America by private plane before he returns to—” and so on.

The elevator stopped and Mr. Wens took the paper and pushed my elbow and we was walking along that soft carpet toward the door.

“Listen,” I says, “can I ask you something?”

“Later,” he says, and he knocked on the door.

“This can’t be happening,” I says to myself. “I seen too many movies, I read too much in them magazines at the beauty parlor. This can’t be happening. It just can’t.”

But it was. There were the two boys in the white head things and there was the gentleman, standing under the light, smoking a cigarette. I held out my fist and opened it and there was the ring with the little beads of sweat on it. I opened my other hand and there was the broken chain. The gentleman that I had just found was a prince fell on his knees and kissed the toe of my slipper. The other two boys put their foreheads to the carpet and their behinds up in the air, and that’s all I remembered, because I went and fainted for the first time in my life.

The first thing I knew was a burp from the fumes of the liquor they must have poured down me—that was sure unladylike. I lay still but kept right on being conscious. After a while I smelled whisky and my head seemed to spin around. But I could see I was lying on a soft bed with my shoes off in the prettiest bedroom you ever saw. Soft rose-colored lights and heavy rose silk curtains pulled all the way across the windows.

The newspaper was on a chair where I could reach it. I pulled it over, and there were two pictures on the front page. One was of those old Japanese men that was in Washington to stop us from going to war with Japan. The other picture was of the little gentleman. It felt funny. The only person I’d ever seen a picture of in a paper that I knew was Willie.

Poor Willie, he sure got his picture taken those days when we was all mixed up with reporters and lawyers. You never know what a pretty little boy will grow up to. Or a girl, either, I was thinking. Look at me, for instance. I sat up and saw myself in a big, round mirror.

My hair knot had come loose and was down all around my shoulders like always, smooth on top and curly towards the ends.

The door opened and one of the boys came in with a little tray with coffee in a teeny little doll cup. I realized when I saw the little sandwiches that I was hungry and no wonder.

The boy laid down the tray on a little table and touched his forehead with his fingers and bowed and went out.

I began to get my senses back. I knew I would have to think in a minute, but before trying that I thought I better eat the sandwiches and drink the coffee. It was black and sweet and strong enough to go out and work for a living. There was a little skinny pot with more in it and three little pieces of candy that was soft and spongy and tasted like roses smell. So I ate it all and drank it all. By that time I was wide-awake and all ready to start thinking, and about time, too.

But before I could do any more than get up and look at myself in the mirror, the door opened and somebody says, “May a chance acquaintance come to call?” And I knew it was Mr. Wens.

“Sure,” I says. “How long was I out?”

“Long enough,” he says. “Did you find the clothes?”

“No, I didn’t,” I says. “What clothes?”

“There,” he says, and pointed to a sofa that had only one arm. On the sofa was a black dress, a cute little black hat, a fur coat that could have fooled a mink, gloves and a black handbag. Beside these was a little traveling bag—black, too—and under the couch were two black pumps and one of my slippers. When I looked back at him he was grinning.

“Who’s dead?” I says, but I didn’t feel like joking. “Whose are they?” I says.

“Yours,” he says. “We’ll get you some more in Mexico City,” he says. “Better get dressed,” he says. “I’ll turn my back and watch the daylight come up over the lake.”

“Will they fit?” I says.

“They ought to come near it,” he says. “I took your slipper and that coat that seemed to fit you.”

“How did you get them at this time of night,” I says, “or morning?”

“There are shops in the hotel,” he says, “and the manager at my urgent request woke up one of his guests who owns one of ’em. He seemed to enjoy choosing things for you.”

“I hope he chose some underwear. I haven’t got any on,” I says.

“So I noticed,” he says, but he never turned around.

So I started dressing, and was I surprised to find everything a near enough fit.

“Listen,” he says. “I want you to go as far as Mexico with the prince, and I don’t want you to ask too many questions why. You are a godsend to the Department,” he says.

“What department?” I says, pulling on stockings as thin as cigarette smoke. “You must have spent all of your money for these things,” I says.

“Mr. Hoover’s money,” he says. “And Mr. Hoover’s Department,” he says. “Do you want to see my identification?”

“You’re all right,” I says.

“How do you know?” he says.

“I know,” I says. “Go on.”

“Well,” he says, “I’ll fix it so the prince will ask you to fly to Mexico with him and his sweets.”

“Who’s she?” I says, and he told me that the people that travel with a prince are called his sweets, all of ’em.

“How will you fix it?” I says.

“Never mind, I think it’s a good thing for you to be out of town for awhile, anyway,” he says.

“Listen, Mr. Wens,” I says.

“Who?” he says.

“Wens, ain’t that your name?” I says. “I remember when I says this is my friend Pimples and what’s your name, that you said ‘Wens.’”

He laughed kind of soft for quite awhile.

“Listen,” I says, “are you arresting me or not? I gotta understand some things.”

“Arresting you?” he says. “What for?” he says.

“About the ring. I thought at first that those four gangsters in the big car was after the gentleman—you know, the prince. Then you was with ’em, then I thought you was arresting me. Now I don’t know. I never heard of dressing anybody up in mourning to take ’em to jail, and besides I didn’t know we had jails in Mexico.”

The brassiere was too loose, so I was tying a knot in it. I was right about Mr. Wens being all right. He kept right on looking at daylight.

“Baby,” he says, “you’re wonderful. Forget it. You’ve done us all a greater service than we could ever thank you for. You see the prince just got tired of people last night after the mayor’s dinner, and somehow he got away from his sweet and into Butch’s place. And while we was looking the town over to find him so we could keep on watching over him till he gets across the border, he disappeared. But God was sure good to us,” he says. “He found a little angel, without any underwear on, to guard the little prince and his rubies, too. You’re a heroine,” he says, “and I wouldn’t be surprised if the English king didn’t make you one of his Dames,” he says.

“You can turn around now,” I says, zipping the dress up at the side, and stamping my feet to see if the shoes were all right, and they were.

“Gosh,” he says.

“Why should I go to Mexico?” I says.

“Well, for one thing,” he says, “this paper here is reporting that the prince came to America to sell

about a bushel of emeralds and diamonds and rubies. Just why he’s selling ’em I can’t tell you, yet. But from what I hear of your friend Pimples and his little playmates, when they read that little item they might get it through their thick skulls that maybe that wasn’t a taillight you was so anxious to pay them a few blue chips for. Don’t you see what I mean?”

And boy, I did.

“Just so,” he says. “They’ll be pretty sore,” he says, “and who could blame them? Now, the prince is leaving around sunrise from the airport, in a very neat little job that he bought himself while passing through Detroit, I have told him that you are in a kind of spot with Pimples and his little pals, and naturally the prince feels that he ought to do anything he can for you, after you risking all to get Hankah back for him.”

“Who’s that?” I says.

“That,” he says, “is the name of the ruby in the ring.”

“Do they christen their rubies?” I says. “I never heard of such a thing.”

“Baby,” he says, “unless I miss my guess, you’re going to learn about a lot of things you’ve never heard about before.”

“But how can I go, now I know that he’s a prince?”

“Forget it,” he says. “He’s as nice a little guy as ever rode an elephant,” he says.

“But who’s going to pay my way back?”

“Listen,” he says, and he came over and stood looking in my eyes, and I couldn’t help thinking how much like the real thing he looked—boyish and nice and ready to grin. “You’ve got to understand what that ruby’s worth to these boys,” he was saying.

“I know, the Wrigley Building. You told me,” I says.

“But more than that,” he says, “it’s sacred. You see it was on the finger of a very special god of theirs.”

“He must have been a giant,” I says. “How’d he lose his pinkie ring?”

“Well,” he says, “a very unexpected earthquake came along and shook him the hell off of his throne. His stone hand, with this ring on his thumb, broke off and rolled down the hill right into the front door of this prince’s old father’s private palace. So this hand has become a kind of talisman. So when his youngest boy started out on this trip, the old prince took the ring off of the stone hand and tied the ring around his boy’s neck and let him come to America with the family jewelry, from which he has already raised about two or three million bucks—for what purpose Mr. Hoover’s nosiest little sleuths, in association with Sherlock Holmes and Scotland Yard and every department in England, including Big Ben, have been unable to find out. But I just mention in passing that whatever it is that he’s over here collecting nickels for seems to be of a good deal of interest to a good many governments.”

Virgin With Butterflies

Virgin With Butterflies